Old San Juan:

Reminiscences 2001

Exhibition review by

José Antonio Pérez Ruiz, Art Critic

English translation by

Pavlova M. Greber, Art Consultant

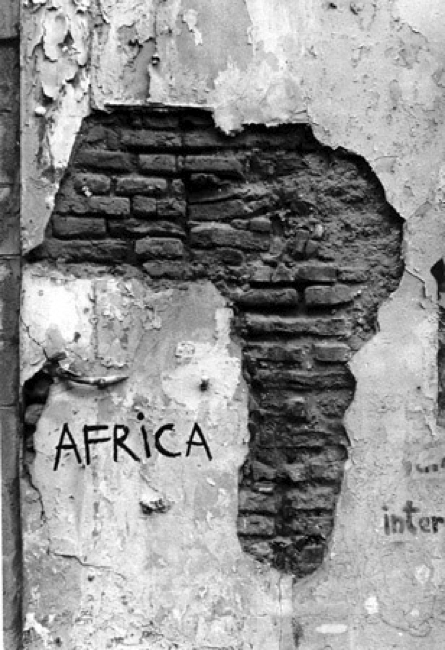

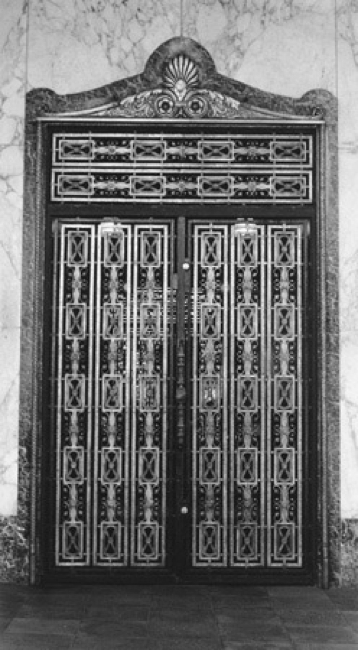

The photographic collection gathered by Chendo Pérez for this exhibition is revealing. These graphics depict the urban situation of Old San Juan at the dawn of the 21st century. It is a sequence where artistic and documentary values come together. Their function is to serve as a reference for new generations to preserve the multi-centennial legacy that survives in that aged urban layout. The details catch the eye, serving as seemingly imperceptible accents that generate the contagious charm that envelops residents and both frequent and occasional visitors. These are nuances that come into play as optical counterpoints. They simultaneously interact as testimonies of different times that coincide in the present. These images capture remnants of the late Gothic that arrived in America. Examples of these are the crenelated walls of the central courtyard of La Fortaleza de Santa Catalina, built during the 16th century following medieval patterns. There are cases where the passage of time led to a structural mestizaje, as seen in the Cathedral or the Church of San José. It can be observed in them that certain spaces of the construction adhere to the patterns brought by the first colonizers. They coexist with timid Baroque presences and strong harmonies of neoclassicism, which is the predominant style of the city. Like much of the hemisphere, notable touches of French influence, the impact of modernism, "Art Deco," and the excesses of those who have followed their own instincts are evident. In short, it offers a fairly comprehensive record of the essence of San Juan.

Chendo has been able to capture the spirit of the places with contemporary artistic criteria. This requires proper use of his working tool, the camera. It goes beyond that, as handling materials to confer drama to the shots demands a development of the tonal scales existing between black and white, through which the vitality of events is transparent. Transcending the mechanism that serves as a starting point is the secret to turning the impression into art. Such gradations establish links evidencing the vital pulsations that have fertilized human action throughout history. The artist's interest goes further, as his intention is to synthesize the human traffic staged in these spaces.

One aspect to note is the preliminary looks required when establishing the angles from which the viewer is facilitated to imaginatively travel to these domains. These are achievements of the perseverance necessary to take light and shadow measurements. It is a search that aims to achieve reciprocity maintained by those antagonistic elements. Such a way of conducting nuances and mid-tones leads the gaze to settle inside the representations. These are ranges studied with the purpose of giving the gaze options to wander at will through these places. Central courtyards provide good examples to understand the aforementioned. In some, vegetation is transformed into its own lyrical agent, accommodating daydreaming. In a way, it leads the observer consciously or unconsciously to measure the incandescences of the reflections. In doing so, it facilitates the sight to undertake escapes into the interior of these enclosures, as happens in the inner arcades of the Centro de Estudios Avanzados de Puerto Rico y el Caribe.

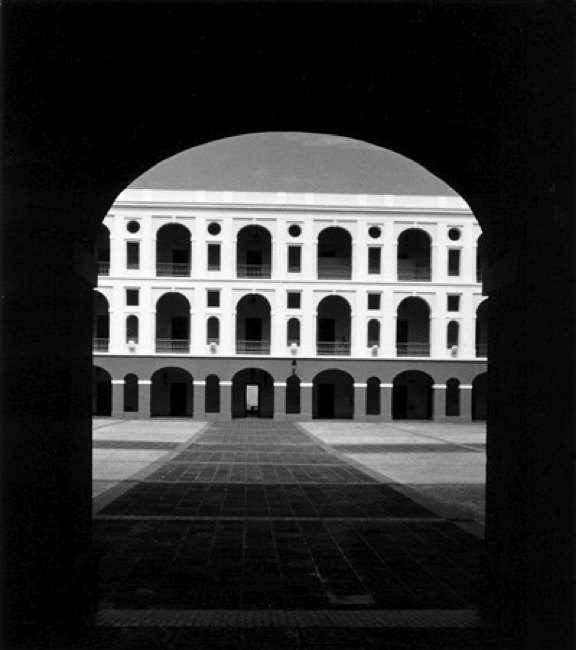

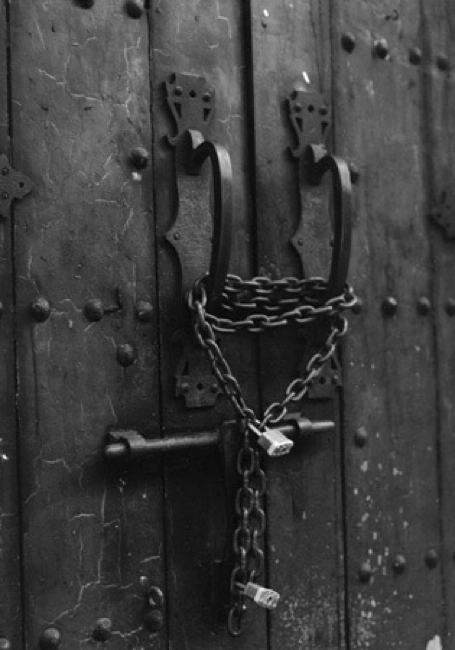

In Ballajá, the artist captured the configurative variations of each level. In doing so, he provides interested parties with an overview that is sometimes not detected by visitors. I have often thought that traditional car tours have accustomed travelers to concentrate on the ground floors of buildings. In fact, speed and the limitations of car bodies limit the visual field of many, and it is possible that they only capture fractions of the panorama. The reaches of these photos captivate those who realize the greatness of these circumstances. Worth mentioning is the way of turning one of the doors of the old barracks into a key point from which to calibrate the contrasts that originate the sense of depth.

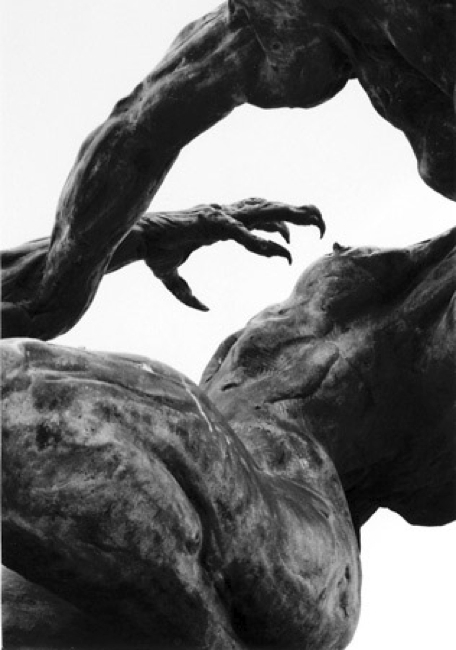

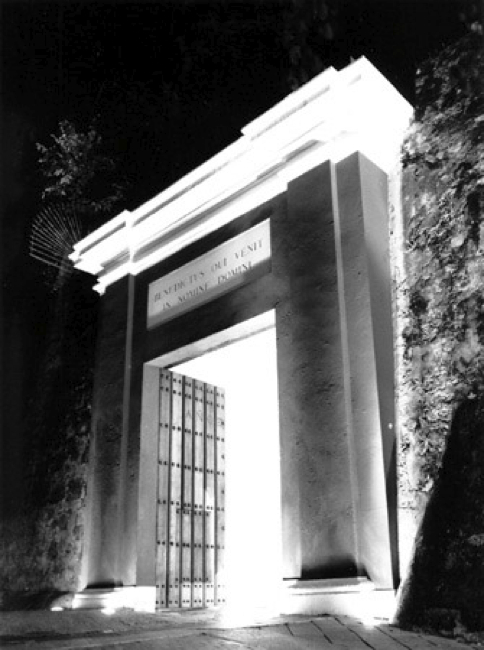

In Chendo's work, there are tendencies to confront us with reality as it is presented to his eyes. However, he takes advantage of everything the environment offers to highlight beauties, without resorting to the cosmetic. To a certain extent, frankness is taken hand in hand with the secrets that the walls, the sacred enclosures, the open spaces, and the people keep. Likewise, we can perceive how the white-painted projections of the hermitage of the Santa María de Pacis cemetery seem to conspire with natural lighting, intertwining with all factors as if responding to a visual goldsmith's work. This snapshot captures the silence of musical eloquence existing in the sacred fields. He chose strategic corners to focus on certain structures that guard the tombs in order to unveil the muted histrionics of introspective pleas for the forgiveness of those lying within them. He extracts from marble vital ductilities destined to bring us closer to plausible attitudes of perennial pain. He has also paid attention to artificial gleams and their projection onto everything that surrounds them. For example, he took the San Juan door in such a way that it seems to lead to an interior of paradisiacal splendor. The inscription on the lintel reads "BENEDICTUS QUI VENII IN NOMINE DOMINI," consonant with that brilliance that awaits the visitor as soon as they enter. Such lights fall in a special way on walls and objects because they gradually fade into space, as we observe in the radiations of the lanterns of the "Paseo de la Princesa," which seem to extend faintly over a landscape of forms hinted at by the mist. Within the buildings, electric lamps spread out phosphorescences in a synchronized manner, as if responding to invariable patterns. It is necessary to indicate that these sparks, as they spread outdoors, provoke dramatic contrasts where shadows extend like sleepwalking strokes. His way of revealing these photos makes them look special, as it transforms them into appropriate spaces to shelter ghosts. The previous statement can be corroborated in the shot of "La Rogativa," a sculpture made by Lindsay Daen, a New Zealander of Australian parents, who made his home on the island. This carving commemorates the rite to which popular tradition attributed the defeat of the English in 1797. The photographer had the insight to place the end of the bishop's crook as if it encircled the silhouette of a full moon, representative of the hopes of a people to find correct directions in times of distress. Another aspect to note is the handling of the lens to make rays sparkle on the silhouettes, marking their contours and offering sensations of movement.

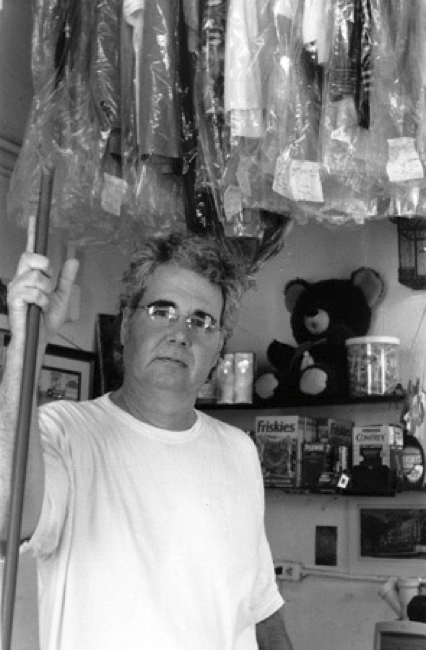

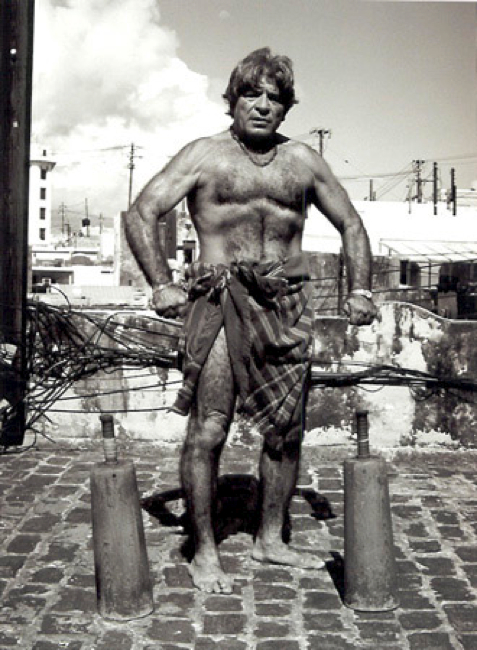

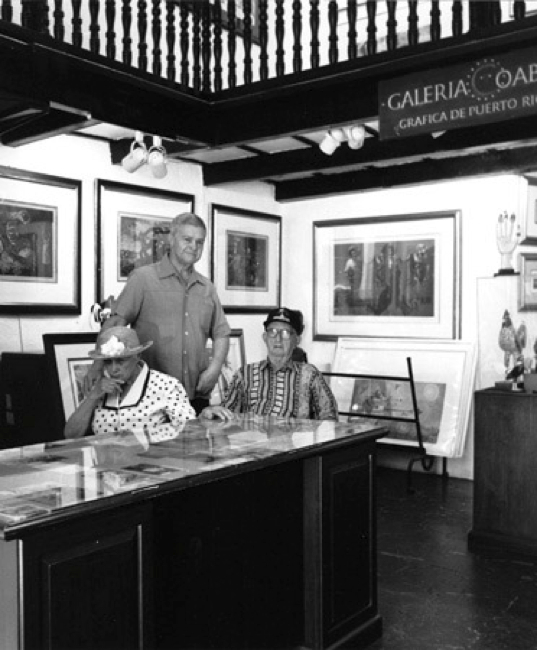

I consider it a great success of Chendo to bring to public attention a representative sample of the beings with whom we come into contact daily in the San Juanian journey. The owner of a laundry constantly providing service demonstrates the dignity he brings to his work. Law enforcement officers are caught in the daily rounds required by their job. He shows the Director of the Coabey Gallery, Jesús M. Díaz Caraballo, in his multiple roles. He is seen amidst the artworks he offers to the public and in his role as a devoted son, constantly vigilant for the well-being of his parents. Others included in his mosaic of characters are public cleaners, parishioners, and wanderers. He seeks to capture in the latter remnants of human dignity maintained despite existential precarities. We discover an eagerness to make visible expectations of hope that announce positive turns in the future.

The exhibition before us comes at a timely moment as it embraces situations and conditions prevailing at the dawn of the third millennium. It takes into account routine and circumstantial aspects of today. Many of the photographs have the potential to generate nostalgias that do not allow the spiritual to dissolve into the turbidities of the moment. They become claims for the preservation of a legacy that we cannot consign to abandonment. It is a document through which current and future generations become witnesses to the inheritance received. In these shots lies the power derived from the enigmas hidden in the historical trajectory of San Juan, Puerto Rico. In that sense, they possess forces analogous to those that come from poetry. It is the city to which Noel Estrada sang of cherished illusions, and "memories of the soul," the San Juan from which we cannot detach ourselves.

José Antonio Pérez Ruiz worked as a history professor at the University of Puerto Rico for thirty-five years; and is the founder of the International Association of Art Critics (AICA) Puerto Rico chapter, an organization he presided over for ten years and of which he is now Honorary President.